Given how precious some members of BMOrg are about people sharing on social media, the choice of “Da Vinci’s Workshop” as next year’s theme is somewhat ironic. Why? Because Leonardo Da Vinci was probably the greatest plagiarist of all time.

The popular theory of history is that Da Vinci was an amazing genius. A painter most famous for the “is she smiling or not” Mona Lisa, he also created 3d perspective. He invented the helicopter; locks in canals; the siege tower; tanks; machine guns; and a broad range of other mechanical devices.

How could one man, a bastard sodomite pauper whose only formal education was in painting, single-handedly come up with all of this innovation? Was he the greatest genius who ever lived? Or did he get some help? From his Demons, perhaps?

How could one man, a bastard sodomite pauper whose only formal education was in painting, single-handedly come up with all of this innovation? Was he the greatest genius who ever lived? Or did he get some help? From his Demons, perhaps?

One theory seems the most plausible, certainly more believable than the official tale.

Gavin Menzies is a former British nuclear submarine commander. He grew up in China, and spent his life sailing the ocean’s currents, on and below the water. His breakthrough book 1421: The Year China Discovered The World, offers a meticulously detailed alternative to mainstream history. Cutting a long story short, maps existed of America, Australia and even Antarctica long before their discovery by the West.

The 1542 Jean Rotz map depicts the coastlines of Africa, Asia, India and China with great accuracy, and shows the east, west and northernmost parts of Australia, some two centuries before Captain Cook. Image via gavinmenzies.net

Gavin Menzies’ next book was 1434: The Year A Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance.

Ignited.

At the time of Da Vinci, the Chinese were at least 3000 years into their civilization. The Ming Dynasty had produced a kind of Encylopedia called the YongLe Dadian. Its books were essentially the sum total of all of their knowledge and inventions.

Emperor Yongle (born with the name of Zhu Di 朱棣) was the third Emperor of the Ming dynasty and he reigned from 1402 to 1424. He was a key figure of the development of the Chinese empire: he transferred the capital of the empire from Nanjing to Beijing and ordered the building of the Forbidden City. Under his reign Admiral Zheng He travelled to the Middle East and East Africa strengthening the trade and diplomatic links with foreign countries…

Emperor Yongle commissioned the Yongle Dadian in July 1403 and the project involved 2169 scholars and compilers from the Hanlin Academy and the National University. Completed in 1408, it was the world’s largest literary compilation, comprising 22,877 chapters bound in 11,095 volumes…The content of the encyclopaedia covers all aspects of traditional “Confucian” knowledge and contains the most representative literature available at that time, ranging from history and drama to farming techniques

[Source: British Library]

It added substantially to the body of knowledge that the Chinese had recorded in 1313 in the Nung Shu, created using movable type a couple of centuries before Gutenberg.

Zheng He was a 7-foot tall eunuch, and perhaps China’s greatest ever admiral and explorer.

The Xuande Emperor would have briefed Zheng He on the background and customs of all the countries the fleet would visit. They had the ideal tool with which to do so – the Yong Le Dadian. This massive encyclopaedia was completed in 1421 and housed in the newly built Forbidden City. 3000 scholars had worked for years compiling all knowledge known to China for the previous 2000 years. The discoveries made on the voyages of Zheng He’s fleet were also incorporated into the Yong Le Dadian. One can go further and say one of Zhu Di’s leading objectives was to acquire knowledge gained from the Barbarians. The best way to acquire knowledge is to share it – to show the Barbarians how immensely deep, wide and old was Chinese knowledge and Chinese civilisation. For this of course they needed to have copies of the Yong Le Dadian aboard their junks and they needed also to brief interpreters about the contents so the message could be propagated.

This vast encyclopaedia was a massive collective endeavour to bring together Chinese knowledge gained in every field over thousands of years under one roof. Zheng He had the immense good fortune to set sail with priceless intellectual knowledge in every sphere of human activity. He commanded a magnificent fleet – magnificent not only in military and naval capabilities but containing intellectual goods of great value and sophistication, a fleet which was the repository of half the world’s knowledge.

Of equal importance were the calendars carried by the fleets. Having been ordered to inform distant lands of the commencement of the new reign of Xuan De, an era when “everything should begin anew,” a calendar was essential to Zheng He’s mission.

Issuing calendars was the prerogative of the emperor alone. Accuracy was necessary to enable astronomers to predict eclipses and comets — a sign that the emperor enjoyed heaven’s mandate. The Shou Shi calendar produced by Guo Shou Jing was officially adopted by the Ming Bureau of Astronomy in 1384. This is the calendar that both Zhu Di and the Xuan De emperor would have ordered Zheng He to present to foreign heads of state. The calendar contained a mass of astronomical data running to thousands of observations. It enabled comets and eclipses to be predicted for years ahead as well as times of sunrise and sunset, moonrise and moonset. The positions of the sun and moon relative to the stars and to each other were included, as were the positions of the planets relative to the stars, sun and moon. Adjustments enabled sunrise and sunset, and moonrise and moonset, to be calculated for different places on earth for every day of the year.

[Source]

Could Leonardo da Vinci have drawn inspiration for his inventions from the drawings in the Chinese encyclopedia? Or is it just hundreds of coincidences that his inventions already existed in China, and he was living in a place bustling with Chinese trade?

Menzies is a fan of Da Vinci. He writes:

In my youth, Leonardo da Vinci seemed the greatest genius of all time: an extraordinary inventor of every sort of machine, a magnificent sculptor, one of the world’s greatest painters and the finest illustrator and draughtsman who ever lived. Then, as my knowledge of Chinese inventions slowly expanded, more and more of Leonardo’s inventions appear to have been invented previously by the Chinese. I began to question whether there might be a connection – did Leonardo learn from the Chinese?

Leonardo drew all the essential components of machines with extraordinary clarity – showing how toothed wheels, gear wheels and pinions were used in mills, lifting machines and machine tools. All these devices had been used in China for a very long time. In the Tso Chuan are illustrations of bronze ratchets and gear wheels from as early as 200 BC which have been discovered in China.

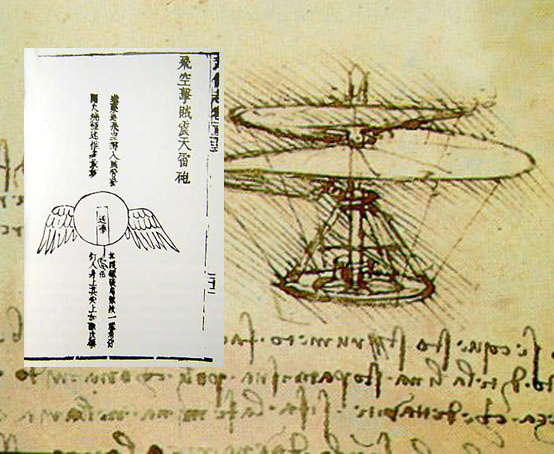

Leonardo is renowned for his drawings of different forms of manned flight, notably his helicopter and parachutes and his attempts at wings. The earliest Chinese description of the possibility of manned flight occurred in the accounts of the short-lived and obscure Northern Ch’I dynasty (ninth century BC). The Chinese had made use of the essential principle of the helicopter rotor from the fourth century AD and by then, helicopter toys were popular in China, a common name being “bamboo dragonfly”. Parachutes were in use in China fifteen hundred years before Leonardo, hot air balloons were known in the second century AD in China and by Leonardo’s day, the kite had been in use for hundreds of years.

Leonardo drew an array of gunpowder weapons, including three variations of the machine gun, which can be seen in the fire lances used in China since 950 AD. Leonardo also drew different types of cannon, mortar and bombard. The Chinese use of bombard is well catalogued throughout the ages.

Comparisons of the machines of Leonard with earlier machines from China reveal close similarities in toothed wheels and gear wheels, ratchets, pins and axles, cams and cam-shaped rocking levers, flywheels, crankshaft systems, balls and chains, spoke wheels, well pulleys, chain devices, suspension bridges, segmented arch bridges, contour maps, parachutes, hot air balloons, “helicopters,” multi-barrelled machine guns, demountable cannons, armoured cars, catapults, barrage cannon and bombards, paddle wheel boats, swing bridges, printing presses, odometers, compasses and dividers, canals and locks.

Even the most devoted supporter of Leonardo (like my family and I!) must surely wonder whether his work’s amazing similarity to Chinese engineering could be the product of coincidence.

The parallels between Da Vinci’s creations and the drawings in the Chinese encyclopedia are striking.

You’ll need to buy the book to see more.

You’ll need to buy the book to see more.My research revealed that Leonardo had owned a copy of di Giorgio’s treatise on civil and military machines. In the treatise, di Giorgio had illustrated and described a range of astonishing machines, many of which Leonardo subsequently reproduced in three-dimensional drawings. The illustrations were not limited to canals, locks and pumps; they included parachutes, submersibles tanks and machine guns as well as hundreds of other machines with civil and military applications.

This was quite a shock. It seemed Leonardo was more illustrator than inventor and that the greater genius may have resided in di Giorgio. Was di Giorgio the original inventor of these fantastic machines? Or did he, in turn, copy them from another?

I learned that di Giorgio had inherited notebooks and treatises from another Italian, Mario di Jacopo ditto Taccola (called Taccola “the jackdaw”). Taccola was a clerk of public works living in Siena. Having never seen the sea or fought a battle, he nevertheless managed to draw a wide variety of nautical machines – paddle wheeled boats, frogmen and machines for lifting wrecks together with a range of gunpowder weapons, even an advanced method of making gunpowder. It seems Taccola was responsible for nearly every technical illustration that di Giorgio and Leonardo had later improved upon…

How did a clerk in a remote Italian hill town, a man who had never travelled abroad nor obtained a university education, come to produce technical illustrations of such amazing machines?

[Source]

The answer, explained with a great deal more depth and evidence in the book, lies to the East:

Well it’s certainly plagiarism…Everything which Leonardo drew were improvements on an earlier Italian, called Francesco Di Giorgio, whose notebooks Leonardo possessed and copied and improved on. And Di Giorgio was not original either. He copied everything from an earlier Italian called [Mariano] Taccola…The source of Taccola and di Giorgio’s inventions was, of course, the Nung Shu passed on by Zheng He’s fleets in 1434.

In the book, the first drawing was of two horses pulling a mill to grind corn, just as Taccola and Di Giorgio had done. Every variation of shafts, wheels and cranks ‘invented’ and drawn by Taccola and di Giorgio are illustrated in the drawings of the Nung Shu. This is epitomised in the horizontal water powered turbine used in the blast furnace. Every type of powered transmission described by Taccola and di Giorgio is shown in the Nung Shu. By comparing Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings with the Nung Shu, each element of a machine superbly illustrated by Leonardo had previously been illustrated by the Chinese in a much simpler manual.

In summary, Leonardo’s body of work rested on a vast foundation of work previously done by others. His mechanical drawings of flour and roller mills, water and saw mills, pile drivers, weight transporting machines, all kinds of winders and cranes, mechanised cars, all manner of pumps, water lifting devices and dredgers were developments and improvements upon di Giorgio’s Trattato di Architettura Civil e militare and his rules for perspective for painting and sculpture were derived from Alberti’s De Pictura and De Statua. His parachute was based on di Giorgio’s and his helicopter modelled on a Chinese toy imported to Italy circa 1440. Leonardo’s work on canals, locks, aqueducts and fountains originated from his meeting in Pavia with di Giorgio in 1490. His military machines were copies of Taccola and di Giorgio’s – but brilliantly drawn.

Leonardo’s three-dimensional illustrations of the components of man and machines are a unique and brilliant contribution to civilization — as are his sublime sculpture and paintings…it is time to recognise the Chinese contributions to his work. Without these contributions, the history of the Renaissance would have been very different.

[Source]

Like most Shadow History that tells a more nuanced story than the mainstream interpretation, Menzies has his detractors – both for his 1421 and 1434 theories. Most do not directly address the massive amount of evidence he presents, choosing instead to pick apart minor details such as “a canal could not have been dug for boats that wide and heavy”. Aside from the fact that if you can dig a ditch, you can dig a bigger ditch, we are talking about books and scrolls. By ship, camel, horse, or even on foot, in the 15th century it was possible to get books from China to the richest part of the world – which at the time was Venice, and had been for almost 1000 years. Cosimo de Medici was hiding out there in exile from Florence at the time Menzies says the Chinese arrived.

Florence was about the size of Burning Man, before the Black Death plague hit in 1348. The Medici banksters used patronage of the arts as a way to control the city from behind the scenes. Like the Borgias, they were famous for poison, torture, and incest. They funded Machiavelli to re-write history for them, then tortured and exiled him when he started to hint at the truth of what they were really up to.

Of a population estimated at 80,000 before the Black Death of 1348, about 25,000 are estimated to have been engaged in the city’s wool industry: in 1345 Florence was the scene of an attempted strike by wool carders (ciompi), who in 1378 rose up in a brief revolt against oligarchic rule in the Revolt of the Ciompi. After their suppression, the city came under the sway (1382–1434) of the Albizzi family, bitter rivals of the Medici. Cosimo de’ Medici was the first Medici family member to essentially control the city from behind the scenes. Although the city was technically a democracy of sorts, his power came from a vast patronage network along with his alliance to the new immigrants, the gente nuova. The fact that the Medici were bankers to the pope also contributed to their rise. Cosimo was succeeded by his son Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici, who was shortly thereafter succeeded by Cosimo’s grandson, Lorenzo in 1469. Lorenzo was a great patron of the arts, commissioning works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli.

A second individual of highly unusual insight was Niccolò Machiavelli, whose prescriptions for Florence’s regeneration under strong leadership have often been seen as a legitimization of political expediency and even malpractice. Commissioned by the Medici, Machiavelli wrote the Florentine Histories, the history of the city. However, Machiavelli was actually tortured and exiled from Florence by the Medici family and the Pope under the pretense of sedition due to his ties to the previous democratic government of Florence and the fact that his work threatened to expose the true nature of their power base and they wished to discredit him. The Florentines drove out the Medici for a second time and re-established a republic on May 16, 1527.

[Source: Wikipedia]

Menzies now has several books as well as globally crowd-sourced research adding to his proof pile on a daily basis.

He has this to say about Florence, where a revolution was going on not just in the arts, but also in math, science and engineering:

Between the acquisition of the port of Pisa in 1406 and that of Livorno in 1421, Florence had enjoyed a continuous economic boom. Florence’s access to Venice enabled her to reap some of the benefits of Venice’s trade with the East. It also exposed the city to an influx of Chinese and other Asians, as we can see from period paintings and sculpture. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who never left Tuscany, painted The Martyrdom of Francescan Friars in the church of San Francesco Siena, depicting Chinese merchants with conical hats. Previously, oriental eyes had appeared in faces painted by Giotto and Duccio. There was a very substantial Chinese and Mongolian population in Florence in the decades after 1434.

For the next hundred and fifty years, Medici power and money fired the Renaissance.

The Renaissance produced an enormous appetite for talent — engineers, astronomers, mathematicians and artists whose individual works were so widely acclaimed that others were inspired to follow with confidence. The Chinese delegation, with their new ideas, fabulous inventions and depth of culture would have made a very forceful impression on Florentine intellectuals, including Paolo del Pozzo Toscanelli. Florence was the ideal loam for Chinese intellectual seeds.

Cosimo de Medici took a dramatic turn after 1434, embarking on an orgy of patronage. He financed exotic palaces and chapels – San Lorenzo, San Marco and the Medici Palace. Cosimo and his brother Lorenzo’s embellishment of the sacristy at San Lorenzo was a notable insertion of science into the very heart of the church: in the little dome above the altar, an astronomical fresco depicted the position of the sun, moon and stars for 6 July 1439, the official day of union between the Eastern and Western Churches signed at the Council of Florence. This scientifically accurate depiction of a particular day’s sky was unfamiliar. The position of the sun, moon and stars for 6 July 1439 were all remarkably accurate. The puzzling question is how did Cosimo’s artist — without the benefit of computer based astronomical tables — know the position of the sun, moon and stars for 6 July 1439?

Someone knew the precise positions of the stars relative to each other, as well as the positions of the sun and moon relative to each other and to the stars. Whoever painted that fresco understood the solar system. This complex painting required years to execute, during which the position of the stars relative to the earth would have changed according to the 1,461-day cycle. It could not have resulted from piecemeal observations over the course of the job – my conclusion is that the artist had access to accurate astronomical tables.

Author James Beck, in Leon Battista Alberti and the Night Sky at San Lorenzo, has shown that the painter was Leon Battista Alberti, perhaps assisted by his friend Paolo Toscanelli. These two were Florence’s leading astronomers and mathematicians in 1439. Alberti in 1434 had accompanied Eugenius IV to Florence, where he met Toscanelli. The most likely explanation of the fresco mystery is that Alberti, who served as the Pope’s notary, met the Chinese delegates and obtained a copy of the astronomical calendar presented by the Chinese to Eugenius IV. The calendar provided the necessary information of right ascensions and declinations of stars to draw the night sky for a particular day and hour.

[Source]

Suddenly, in the space of decades, the Italians invented all the things the Chinese had over thousands of years! And it was Da Vinci who did it all. Sounds like spin to me.

Naturally, there’s a Snopes on it. It fails to explain why Native Americans look like Chinese Mongolians, ride horses like them and share their DNA. It doesn’t explain multiple maps that have been found pre-dating Columbus’ voyage. Snopes also does nothing yet to address a newly emerging theory that the first Americans were Australians.

Like always, do your own research. The book 1434 is a great place to start. The truth is out there, and thanks to the (still mostly uncensored) Internet it’s not even that hard to find. Think for yourself and question convention.

I’m hoping for lots of Chinese food being handed out at Burning Man 2016.

[Update 11/3/15 12:14pm]

An art historian has found many problems with BMOrg’s version of history.

Pingback: The Truth About Da Vinci [Update] | In Pursuit of Happiness

You are close but you have to take it back even further to North America 10,000 years ago whom had ships sail to Egypt (leading to the pyramids) and then Egypt went to China and China to Europe.

In a short post, the most compelling evidence for this is the use of the tobacco plant in ancient Egyptian mummification, a plan native only to South America with no evidence of Egyptian being a seafaring culture.

I’m with you. Plenty of evidence for “pre-historic” links between South America and Egypt.

They may have been descendants of sea-faring Australian Aborigines. Or genetically engineered hybrids created by higher order beings, such as the Annunaki.

You’re saying the Annunaki were historical figures? I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s what you mean, just want to be sure I get what you’re saying.

There’s a whole TV series on it. “Ancient Aliens”.

Ha, I know. I know. On the “History” Channel. And this is something you take to be non-fiction?

Watch the show. These places really exist. These drawings and paintings really exist. Ancient texts really exist. Unexplained archaeology really exists. That’s why it’s on the History channel, because they are showing you real things that are on this planet, not camera trickery or forgeries.

“I don’t believe in higher-order beings, but for recreation I spiritually worship a giant effigy”

Well, I don’t really worship the Man, but as a communal ritual, it’s a pretty good one. Ritual for me is more about reminding myself, in the company of others doing the same, of some important things like non-attachment and whatnot. Not sure if that’s “worship” in the sense that I don’t believe the Man is anything other than a wooden symbol.

The History Channel is nothing but hilarious these days. I’ve watched Ancient Aliens. It’s good fun, but jeez, talk about wild speculation.

I find their wild speculation more belivable than the missives from the Borg.

Well I don’t look to the BMORG for historical analysis.

Uh…. you know the 2016 NV burn theme?

http://blog.burningman.com/2015/10/brc-art/burning-man-2016-da-vincis-workshop/

Did you come up with that historical analysis, or did they?

Hey, if you ask nice, maybe Burnersxxx would do a post about that! 🙂

http://blog.burningman.com/2015/11/highbrow/can-burning-man-balance-the-art-and-history-in-art-history-should-it-have-to/

For chrissakes.

He was very probably inspired by the Chinese; I agree with Menzies that the Venice treasure ship documents got to Leonardo. But many of the ideas Leonardo drew were not to be found in Chinese manuscripts.

Fascinating stuff, I need to know more!!

For me the book to start is Fritjof Capra for sure

Fritjof Capra “The Web of Life” was a life-changing book for me, much more so than attending Burning Man.

Spolisport! Facts, facts, facts. That is all you have. You are really bad at this sucking-up-to-the-Borg thing. Sure, Leonardo and Florence are are the heart of the re-discovery (renaissance) of all these old things, but that is what the NV burn is, on a much smaller scale.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_iOXc7WQoMho/TKuvn_bEgmI/AAAAAAAAAPs/TqtCPEsGVWs/s1600/wicker+man+burning.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:001132_Der_brennende_Mann-Brauch_(Wikcker_man)2013_in_Wola_S%C4%99kowa,_Sanok.JPG#/media/File:001132_Der_brennende_Mann-Brauch_(Wikcker_man)2013_in_Wola_S%C4%99kowa,_Sanok.JPG

“A wicker man was a large wicker statue purportedly used by the ancient Druids (priests of Celtic paganism) for sacrifice by burning it in effigy, according to Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentary on the Gallic War).[1][2] Contradicting the Roman sources, more recent scholarship finds that “there is little archeological evidence” of human sacrifice by the Celts, and suggests the likelihood that Greeks and Romans disseminated negative information out of disdain for the barbarians.[3] There is no evidence of the practices Julius Caesar described, and the stories of human sacrifice appear to derive from a single source, Poseidonius, whose claims are unsupported.[4]”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wicker_man

http://wickermanburn.org/